Have you ever heard of extrinsic motivation? What about intrinsic motivation? If you’re like me prior to writing this article, the answer is no, and it could be holding back your success as an entrepreneur.

Here’s why:

If you want to start your online business and expect to make it through the many difficult challenges ahead of you, you’re going to need a ton of motivation. But you don’t need just any type of motivation; you need the right kind, that can give you the powerful inner fuel you need to charge ahead with your dreams and start making money.

How to Use Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Start Your Business

Why Motivation Isn’t What It Seems

Understanding Extrinsic Motivation

Understanding Intrinsic Motivation

The Power of Integrating Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation

A Final Breakdown of the Motivation Process

What do you usually do at first to motivate yourself? You maybe open your Instagram to read motivational messages. You go to your Facebook feed for the same.

You’re not alone. People crave motivation. That’s why inspiration blogging is such big business. Like cracking a Red Bull, people are looking for something that will drive them; something that pushes them closer to their goals.

The problem is, that’s not how motivation really works.

Forty years ago, a pair of psychologists found motivation has two sides: an extrinsic (or external) one, and an intrinsic (or internal) one. It’s a super nerdy distinction, but understanding these two types of motivation will make a big difference in how you inspire yourself to overcome all the challenges that you’ll face as you start your business.

In this post, you’ll learn how extrinsic and intrinsic motivation work and how you can use them to get your business off the ground once and for all.

Why Motivation Isn’t What It Seems

Motivation is often seen as a “thing” you can obtain, like an apple or a car. If you want motivation, you only need to find it and learn how to use it. But is motivation as concrete as that?

Some psychologists would say so.

Around the late 19th century, psychologists from the behaviorist school started to hypothesize that if you don’t feel motivated, it’s because there’s something lacking—a reward (like praise or money) or a punishment. Add that reward (or punishment), and find motivation.

At first sight, that idea seems to make sense. For example, if you want to lose weight and want to motivate yourself to train, you could tell yourself you can eat a small pizza after a workout (your reward). A small pizza wouldn’t hurt you, right? You’ve done your job; now you need the reward.

In a similar vein, you can get a personal trainer who screams in your face every time you go to the gym so you push yourself really hard and burn as many calories as possible. Painful, but that punishment would probably help, at least in the short term.

You can easily see the limitations of this mindset. You don’t need to balance the act of eating pizza with training—you should also think of pizza as unhealthy and limit it in your diet. The same applies to punishment. Your sense of motivation shouldn’t be someone screaming at you, but from the desire to look thinner, be healthier, and feel better.

In other words, your reward (or lack thereof) isn’t stopping you from losing weight; your inner motivation is.

In 1977, Richard Ryan, a soon-to-be clinical psychologist with a philosophy major, and Edward Deci PhD, an experimental psychologist with a background in math, met at the University of Rochester and had a conversation that would change their lives—and the lives of many others.

Ryan and Deci realized that there was a disconnect between the widely accepted behaviorist theory of motivation—the one that uses rewards and punishments as a tool for motivation—and reality.

In execution, these supposedly powerful rewards don’t actually work all that well.

So Deci and Ryan developed the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) of motivation, which toppled the dominant the Behaviorist school, and changed the way psychologists think of motivation.

The Self-Determination Theory states that people certainly can be motivated externally—by money, or a desire for social approval, for example—or internally—by passion for the project itself.

They didn’t reject external rewards altogether. Instead, they said a reward (or punishment) isn’t the only thing that matters, and most importantly, isn’t the best way to motivate someone.

In their 1985 book, Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior, which has been cited over 37,000 times according to Google Scholar, Deci and Ryan explain:

We distinguish between different types of motivation based on the different reasons or goals that give rise to an action. The most basic distinction is between intrinsic motivation, which refers to doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable, and extrinsic motivation, which refers to doing something because it leads to a separable outcome. Over three decades of research has shown that the quality of experience and performance can be very different when one is behaving for intrinsic versus extrinsic reasons.

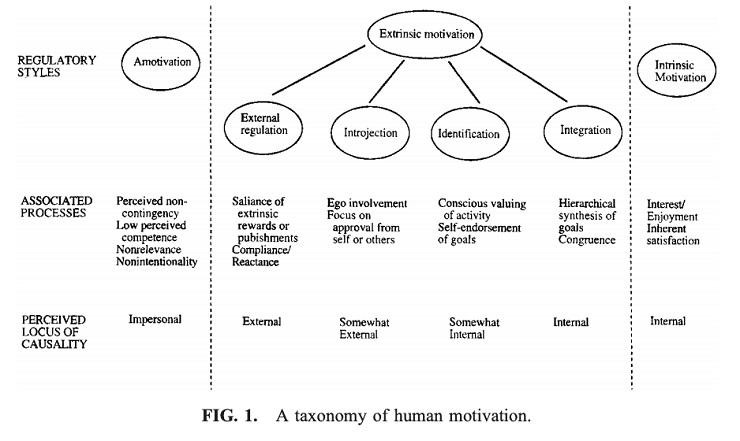

According to the authors, motivation isn’t a concrete resource like, say, willpower (as explained by Roy Baumeister), but a broad set of emotional levers whose range can affect the way we act. According to their theory, humans go through three stages of motivation, what they call the “Organismic Integration Theory (OIT),” or “the taxonomy of human motivation.”

Stay with me. 🙂

In this image, you can see the range of motivation levels across three stages:

- Amotivation: You don’t care about the task.

- Extrinsic motivation: You are motivated by the external factor.

- Intrinsic motivation: You are motivated by your inner satisfaction.

According to the psychologists, amotivation means that you lack an intention to act. When you’re told you have to make cold calls to start a business but you feel like it’s pointless, you are amotivated. There are multiple reasons why this can happen, but the fact is you have neither an internal nor an external motivation to pick up the phone. You don’t know why you have to do it or what you get in return from the activity. And considering cold calling is kind of scary, you’re never going to do it.

Deci and Ryan then explain there are three causes for amotivation:

- A lack of value in the activity (Ryan, 1995)

- A feeling of incompetence (Deci, 1975)

- A lack of belief that the task will bring the desired outcome (Seligman, 1975)

So maybe you don’t see how the calls are important, or you have no experience doing it and feel like you’ll be ineffective, or you don’t believe it will work. Whatever the case, there’s a reason why you feel like this, and avoiding it will not help you at all.

Amotivation is the one state on which all psychologists can agree. Where it gets interesting is Deci and Ryan’s segmentation of motivation; one that separates between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation.

To them, the way you motivate yourself—either extrinsically or intrinsically—is what truly matters.

Let’s take a look at how each of these two types of motivation work.

Understanding Extrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic motivation exists when you are motivated by an external factor or a specific outcome. It’s what drives you to do things for tangible rewards or pressures rather than for the sake of doing it. When you are extrinsically motivated, you have to explain to yourself why you should do it—that is, for the reward or to avoid the punishment.

Not all extrinsic motivation is alike, however. As you saw in the image above, there are four levels of this motivation, based on the way you process the external factor:

- External regulation: You do the task because you have no choice. In this stage, people feel “controlled or alienated.” Most often than not, minimum wage employees and low-level bureaucrats are externally regulated, which is why they’re known for their low-quality work and lack of interest in helping others.

- Introjection: You do the task because you feel like it’s the best thing for you or your social group. Your intention is to “enhance or maintain your self-esteem and the feeling of worth.” Most employees seem to be in this state; while they like their jobs and are willing to do them, they do it for the money, status, or power.

- Identification: You value the task you do and you are somewhat internally motivated to do it, despite the fact you have to do it. A good example is a worker who’s happy with their job and likes to work and share time with coworkers, and feels valued. They even go a bit beyond their mandatory responsibilities to help the company move forward.

- Integration: You have absorbed the values of the task you’re forced to do, like when someone says they have “the best job in the world.” You don’t care about the money or the time you spend on your job; you do it because you love it and have integrated the external motivation as your own.

The problem with externally regulated processes is that they decrease the quality of the work done—the subject under this circumstance does the task to gain the reward or avoid the punishment. As you can imagine, you want to avoid this kind of situation, both for yourself and for others.

The more autonomous the extrinsic motivation (the closer it its to the integration phase in the right side of the image above), the better it is for the individual, as it’s been associated with:

- Greater engagement (Connell & Wellborn, 1991)

- Better performance (Miserandino, 1996)

- Higher quality learning (Grolnick & Ryan, 1987)

- Greater psychological well-being (Sheldon & Kasser, 1995)

But if extrinsic motivation isn’t ideal, we must ask ourselves, why can’t we just be intrinsically motivated? Can’t we switch that good stuff on? Let’s take a closer look.

Understanding Intrinsic Motivation

Intrinsic motivation is when you are motivated by internal factors. You are driven to do things just for the fun of it, or because you believe it is a good or right thing to do.

Most creative hobbies are intrinsically motivated. When someone collects stamps and coins, paints a tiny tin soldier, or learns to dance, they put all their energies and care into it. Few people carry that amount of passion into the workplace.

It’s hard to say if there’s a way to develop intrinsic motivation—it comes from within yourself, after all. If there was something that could use to trigger your intrinsic motivation, then it would be extrinsic.

The key lies in integrating intrinsic motivation into extrinsically motivated tasks.

That is, if you can bring some intrinsic motivation to work with an otherwise extrinsic form of motivation, you can make yourself (as well as others) more motivated. You will enjoy your tasks more, even though you’re doing them for an external reason (like a paycheck).

Let’s take a look at how you can integrate intrinsic motivation with an extrinsic one.

The Power of Integrating Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation

When you want to start your business, you probably feel an inner motivation to do it. There’s something wrong in the world you want to fix. You have something the world needs to see. You want to help others. But then, as soon as you hit the ground running, you feel scared, worried, and doubtful. You feel like you can’t do it. Back to amotivation.

Before you try anything, the first thing you need to realize is that there’s no real way to manufacture intrinsically motivation.

If you don’t feel motivated to do something—do cold calls, set up a meeting with an investor, develop a partnership—you can’t magically snap yourself out of your amotivation.

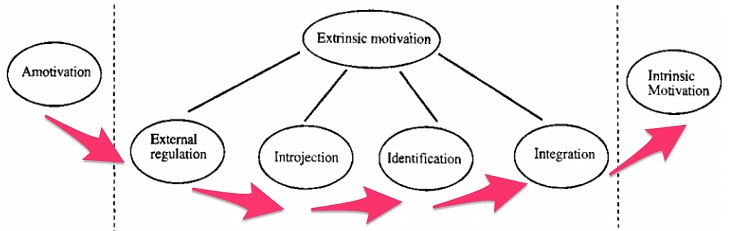

Rather, your goal is to feel an identification and become integrated with the values and processes of any given task. The closer you can get to such a state, the more “self-regulated” your behavior will be; that is, the more intrinsic your motivation will be.

Your goal should be to get as close as possible to the right side of the image below, playing up the intrinsic motivation as much as possible. You want to have a deeper purpose behind your tasks, in other words, not just money.

Deci and Ryan found there are three factors that play into this increased intrinsic motivation.

1. The first one is that the individual feels like his task has a greater purpose. As the authors explain:

The groundwork for facilitating internalization is providing a sense of belongingness and connectedness to the persons, group, or culture disseminating a goal, or what in SDT we call a sense of relatedness.

If you want to feel motivated, start by recognizing that an external motivation is either money, status, recognition, skills, or experience. These goals are the “external regulators,” as the authors call them. They are just the beginning, however.

To develop that sense of relatedness, focus on your company’s mission, values, and goals. Here’s where having core values matter a lot. You need to think about how you can tie your values and goals together with your company’s. Such integration will help you develop a productive workplace culture and make both you and your employees happier.

An interesting example of such integration between an employee and a company’s values are Apple’s geniuses, who are willing to get paid below industry average just to work for the company.

Ron Johnson, former SVP of retail operations, who was responsible for setting up Apple stores worldwide, explains how they achieved this in a Harvard Business Review interview:

Getting a job on the sales floor at Apple today requires six to eight interviews, including with the person who runs the entire local market. One result of that intensive process is that when people are hired, they feel honored to be on the team, and the team respects them from day one because they’ve made it through the gauntlet. That’s very different from trying to find somebody at the lowest cost who’s available on Saturdays from 8 to 12.

Does Apple have to monitor their geniuses and make sure they serve their customers well? Not at all, because they know their geniuses will do it for the pleasure of working for Apple and selling the best products in the industry.

2. After relatedness, the next key to fostering your intrinsic motivation is to develop a feeling of competence.

If you have ever had a boss tell you can do something because “you’re are the best at it,” or that you have to do something hard because “you can handle it better than anyone else,” then unconsciously they were trying to increase your feeling of competence, and therefore, motivation.

3. Finally, you must have autonomy in the tasks you implement, which the researchers defined as:

…the critical element for a regulation being integrated rather than just introjected. Controlling contexts may yield introjected regulation if they support competence and relatedness, but only autonomy supportive contexts will yield integrated self-regulation.

The idea of autonomy is close to US General George S. Patton’s advice: “tell people what to do and let them surprise you.”

Give yourself (or other people) autonomy to carry out a task, and they’ll figure out the best way to do it. Even if they’re inefficient—something you can fix later on—they will feel like they have control over the task, and thus feel motivated to do it.

How to Motivate Yourself: A Simple Guide

Let’s take these three suggestions Deci and Ryan have come up with and illustrate them in a simple example. Let’s go back to our example of having to make cold calls to get a few clients for your consulting business, but you don’t feel motivated to do so.

Based on what we know about motivation, some reasons that could explain your behavior include:

- You have a feeling of incompetence towards this skill.

- You don’t feel a connection between the task and the goal of generating revenue.

- You feel like cold calling makes you a bad person, something that violates a personal value of yours.

- You don’t feel like you have the autonomy to make the cold calls in the way that best suits you (this could mean you have someone telling you how to do them).

To overcome such a state of amotivation, you can start with an extrinsic goal such as revenue. The goal of hitting $10,000 of monthly revenue is a good way to start your motivation.

You can then continue by focusing on developing your sales skills, using research or role playing. You can also get a coach to train you and mentor you in this process so you can increase your feeling of competence.

Then, to develop a feeling of relatedness, you can remind yourself that this exercise is a way to gain experience and skills as a founder, an identity you feel a close personal association with.

Finally, you could develop the autonomy necessary so you can carry the cold calls in a way that makes you feel like an honest salesperson.

The same applies if you want to motivate an employee or partner. Give them a clear sense of a larger purpose (relatedness), assign tasks that best fit their skills (competence), and give them leeway to do it their way (autonomy).

In other words, tell them what you want and why you want it, trust them, and let them do their job. If you hired them correctly, they’ll do what you wanted them to do. There’s no need to micromanage people or threaten them; if you work with smart people, they’ll do it.

To truly push the intrinsic motivation of people, the authors conclude that:

To fully internalize a regulation, and thus to become autonomous with respect to it, people must inwardly grasp its meaning and worth. It is these meanings that become internalized and integrated in environments that provide support for the needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy.

If you tell someone they must do something because it’s the best for the company, they’re the best to do it, and they can do it in the way they best deem possible, you will increase their intrinsic motivation, even though they’re still being extrinsically motivated.

Give yourself and your employees meaning, and you will open the doors of intrinsic motivation.

A Final Breakdown of the Motivation Process

I can safely say this is the nerdiest post ever published at Foundr. 🤓

After reading so many academic and abstract words, you might still be thinking, “How on earth can I apply this in my life?”

Here’s the how to, in summary:

Start with a definition of the goal that motivates you. There’s no shame in saying you work for money or you want to lose weight to look hot. If there’s something much greater than an external factor, then awesome. What matters is that you define that clearly.

Then, think where you are in the taxonomy of human motivation graphic. Are you intrinsically motivated? Are you barely convinced of the task and are doing it because someone else is telling you to do it?

Based on your answer, and assuming you’re not intrinsically motivated, think how you can integrate your own values into the extrinsic goal.

If you’re being told to make phone calls and close sales, do you value helping people? If so, think of the sales-closing goal as a way to help people—and make money in the process.

If your loved ones are telling you to quit smoking, do you value playing sports? If so, think of your new habit of not smoking as a way to run longer, faster, and with more enjoyment.

Finally, think how you can find a bigger meaning behind your goal, feel more competent doing it, and be more autonomous while you’re working on it.

Mastering motivation is a continuous process that can make you a better human being in every aspect of your life. You only need to find what’s stopping you to grasp the inner fire of passion, ignite your full energies, and start and grow your business.

What is it that you are trying to find motivation for? Share your ideas in the comments below.