For the past half hour I’ve been finding myriad ways to avoid starting this article. I made a drink, posted a photo to Instagram, read over my notes a couple of times, checked Twitter more than once. Times like these I scoff at the irony that I’m writing about the exact thing I’m struggling with.

If only I had abundant willpower, this article would have been written by now. Or even yesterday.

I’m sure you’ve felt like this before. You see the stack of work waiting to be done, and think about all the distractions that took up the last couple of hours of your time, and wish for the willpower to focus and get things done.

The good news is, it’s definitely possible to improve your willpower.

buy vidalista online buy vidalista online no prescription

It’s not just something you’re born with.

But before we explore how to improve it, we need to understand how willpower works.

How Does Willpower Work: Two Competing Theories

Willpower is a tricky thing to understand. Scientists have been working on it for years, but so far they haven’t come up with a single, proven explanation for how it works.

buy intagra online buy intagra online no prescription

There are currently two competing theories, however, which both have merit and can give us ideas on how to increase our own willpower.

Willpower as a muscle

A popular theory is that willpower is a finite resource, like muscle strength. And, like a muscle, the theory states that we can improve our willpower by exercising it.

This theory was proposed by Roy Baumeister of Florida State University, and his theory states that each temptation we resist depletes the amount of willpower we can rely on for the next temptation.

That means after resisting opening your inbox when you first start work, then resisting checking your phone when your mind starts to wander, then resisting taking a break when you’re only 15 minutes into a task, when a colleague interrupts you to ask about your weekend, you welcome the distraction because you have no self-control left with which to resist it.

Baumeister’s theory held up in a study that asked participants to resist eating chocolate before giving them a puzzle to work on. The puzzle required willpower to concentrate on solving it, and the study found resisting the chocolate first depleted the amount of willpower participants had to rely on when they needed to make themselves focus on the puzzle.

But another study showed how, using Baumeister’s theory, we can practice exercising willpower to get better at it. The study first tested participants to see how much willpower they had, then asked them to straighten their backs every time they remembered to do so for the next two weeks. After the two weeks had passed, participants were tested again, and were found to have increased their willpower.

Willpower as competing impulses

Another theory of willpower comes from George Ainslie, author of Breakdown of Will.

Ainslie’s theory is that we use willpower to overcome competing impulses that exist within us. For instance, you might have an impulse to run a marathon this year, and another to run every morning as part of your training, but when your alarm goes off you might recognize another impulse popping up: one to stay in your warm bed and sleep a little longer.

Ainslie says we can have short-term and long-term impulses, and good and bad impulses. They all compete, and exercising our willpower is like a bargaining game that happens inside us.

The closer in time an impulse becomes, Ainslie says, the stronger it is. This is why the impulse to stay in bed is so hard to overcome: it’s the most immediate impulse, and thus stronger that your impulse to run a marathon, which is far away in time.

How to Improve Your Willpower

Say ‘I don’t’

If you’ve ever tried a diet, you’ll know how uncomfortable it can be to have to tell a dinner or party host, “I can’t eat that at the moment.” It’s not only awkward, you both know you’d love to eat the delicious cake/lasagna/pudding on offer, but you’ve set rules for yourself that say you can’t.

A study of this situation found that saying “I don’t eat that” instead of “I can’t” actually works much better. Participants were better able to resist temptation when they used the phrase “I don’t.”

Whereas “I can’t” reminds you of your limitations, saying “I don’t” taps into your own perceptions of yourself and your behavior, which seems to have some effect on willpower.

Try using this phrase at work when a colleague asks you to chat while you’re working on an important project, or you see an email notification while you’re trying to focus.

Set clear rules

Based on his theory of competing impulses, Ainslie says creating clear boundaries for yourself can make it easier to avoid giving in to impulses that aren’t good for you. For instance, a vague plan to “check email less often” doesn’t help you decide whether or not to check your email each time you feel like doing so. This approach leaves you relying on willpower.

But making clear rules like only checking email when your main task for the day is finished, or only checking email after lunch can make those decisions easier in the moment.

Change your environment

There’s a fancy term called “choice architecture,” which basically means we make decisions based on our environments, so changing our environments can help us make better decisions. Products on eye-level shelves in the supermarket sell better than those down low, because it’s convenient for us to look at those shelves. We don’t even realize we’re doing it.

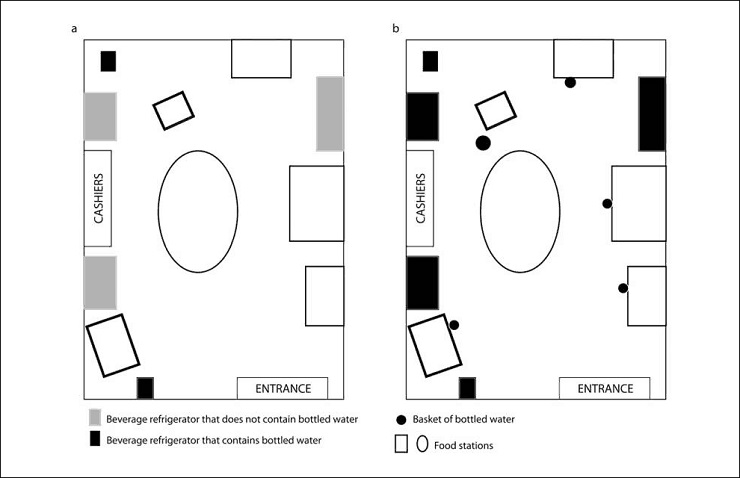

One study tested how changing a hospital cafeteria would affect which food and drinks people bought. The researchers didn’t mention the changes to anyone, but they tested adding more bottled water around the cafeteria, and adding it to all the fridges that held soft drinks. Sales of bottled water increased, and soft drink sales decreased, simply because the healthier option was convenient and obvious.

Image credit: American Journal of Public Health, April 2012 via jamesclear.com

To put this into practice yourself, think about ways to make good habits easier and more convenient, while making it harder on yourself to do the things you want to avoid. The harder it is to do something, the more willpower it takes to force yourself into it, so if it’s a lot of effort to get to the gym, you’ll give up quickly. But if it’s easy to go to the gym and hard not to, you won’t have to use willpower—you’ll do it anyway.

Disconnecting your computer from the internet when you need to focus on work can make it just hard enough to quickly check Facebook or Twitter that you won’t bother. There are also some handy web apps that block access to the internet or just certain sites for a set period of time. Taking social media apps off your phone can make it uncomfortable enough to spend your free time browsing a timeline that you’ll stop. Keeping a book on your desk, or an ebook app on your phone’s home screen can make it more convenient to read, so you’ll spend your free time learning, rather than mindlessly swiping through gifs.

If your meetings take too long, make them more uncomfortable so you’ll naturally want to get them finished quickly. Make everyone stand up the whole time, hold them in a cold room without heating, or ban notetaking so everyone has to remember what’s happened, and no one will want the meeting to run for long.

Make ‘if, then’ plans

Walter Mischel, a professor of psychology at Columbia University, once conducted an experiment that’s since become famous. It’s so well-known, in fact, that he’s now known to some as “the marshmallow man.”

The experiment had young children sit in a room with a treat of their choice, such as a cookie or marshmallow. The children were left alone with the treat, and told they could eat two treats if they waited until the researcher returned. If they gave in and ate the treat in front of them, though, they wouldn’t get a second one.

The study is often mentioned in discussions of willpower, as the it followed up with participants later and found those who resisted temptation had better SAT scores, coped better with stress, and were (a little) thinner.

However, one important part of the research is often overlooked. Mischel says people too often miss the study’s finding that self-control can be taught.

The children who were able to resist temptation in order to earn a second treat used strategies like making up a song, covering their eyes, or pretending the treat was something else, like a piece of wood. For those children who didn’t already know to use these strategies, Mischel says they were able to be taught, and thus improve their ability to resist temptation.

Mischel says willpower comes down to how we think about temptations, and changing our thinking—as the successful children did—can make it easier to hold out.

One approach he suggests is creating an “if, then” plan—essentially making the decision for ourselves ahead of time. An “if, then” plan might be something like, if it’s before noon, then I won’t check my email. Or, if it’s a Monday or Wednesday, then I’ll go to the gym.

“We don’t need to be victims of our emotions,” Mischel says. Using tricks like an “if, then” plan to change how we think about temptations can help us improve our willpower. And, as the children in Mischel’s study showed, sometimes a distraction is the best way to avoid temptation.

It’s funny how once you get into a task you’ve been putting off, it’s rarely as bad as you thought it would be. I’ve been so focused on this article since I got started that I’ve barely thought about the temptations all around me that could have derailed my writing session.

But getting started is often the hardest part, so I’ll be keeping these strategies in mind to boost my willpower, just in case.

What about you Foundr family? How do you supercharge your own willpower? Got any tricks for staying on task?